Understanding The OTCBB

What is the OTC Bulletin Board?

What is the OTC Bulletin Board?

What is the OTC Bulletin Board?

What is the OTC Bulletin Board?

What is a Prospectus?

What is a Prospectus?

What is Global Finance?

What is Global Finance?

What is the International Finance Corporation?

What is the International Finance Corporation?

Finance Management Defined:

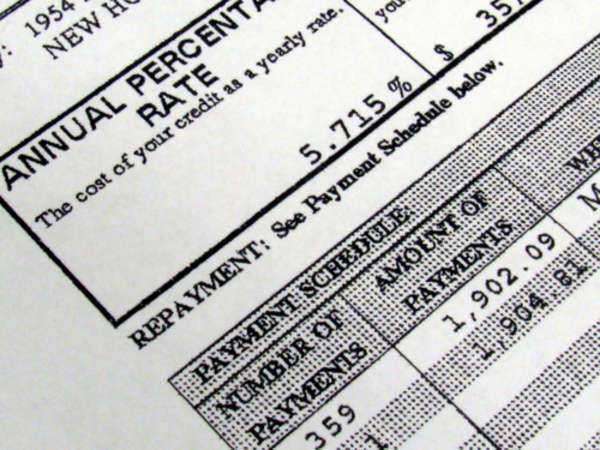

What does APR mean?

What does APR mean?

APR (annual percentage rate) is an economic variable used to describe the current interest rate for a whole year.

APRs are attached to credit cards to signify the interest payments attached to their specific line of credit. The APR of a credit card is outlined in the card’s disclosure statement. Many cards have variable APRs which will attach higher or lower interest rates depending on the spending habits of the card user and the items being purchased

The annual percentage rate is the percentage of interest paid for a 12-month period, meaning, if an individual possesses an APR of 10% their monthly interest percentage is .833%. The monthly interest is the amount that the issuer will charge to the remaining unpaid balance per month. For example, a card with an 18 percent APR has a monthly rate of 1.5%. If the cardholder has an unpaid balance of $500, the 1.5% is attached to the remaining balance and the holder is forced to pay an additional $7.50 each month.

The APR is listed as a percentage and typically attached to a credit card to describe the additional payments (used to satisfy the individual’s interest obligation) that the borrower is forced to pay to for the use of credit.

The APR is a finance charge expressed as an annual rate and takes the form of two specific definitions: the nominal APR and the effective APR. The nominal APR is the simplified interest rate delivered as a yearly percentage while the effective APR is the compound interest rate, which includes a fixed fee.

The nominal APR is calculated as the rate delivered for a payment period multiplied by the number of payment periods in that specific year.

The APR is delivered as an annualized rate rather than the monthly fees or rates that are typically applied to mortgages or other long-term loans.

Factors that Affect an APR

The APR on a credit card will fluctuate based on a number of factors and variables, the most critical of which is the holder’s credit history. Additionally, credit card APRs may change over time as interest rates, the Federal Reserve rate and the prime rate fluctuate to control inflation and to encourage borrowing.

Low APR Credit Cards

As a result of these fluctuations and factors, low APR credit cards today may not appear to be low APR credit cards in 5 or 10 years. Given the instability of the credit market and other negative macroeconomic issues present today, low APR credit cards contain an APR between 8 and 12%. Very rarely will an individual obtain low APR credit cards with a rate below 10 percent; however, the majority of card issuers will offer 0 APR for a fixed amount of time.

Those individuals with higher credit scores will be awarded with a lower APR. Lower APR credit cards are awarded to an individual with a higher credit score because of the mitigated risk of default—the issuer of the card views the individual as a safe investment and therefore grants the individual with the ability to possess 0 APR credit cards or credit cards with low APRs. The variables that calculate the APR can fluctuate upwards to 50%, meaning some cards may carry an APR of 50% while others may have an APR of 0.

The APR is only attached to the remaining balance of a credit card. If the individual fails to pay the complete balance owed and opts instead to pay the minimum balance, the APR will be attached to the remaining balance and then carried over to the following month.

What is a Capital Gain?

What is a Capital Gain?

What does Amortization mean?

What does Amortization mean?

What is Equity?

What is Equity?

The term ‘equity’ refers to interest or the residual claim of a class of investors in assets once all liabilities have been fulfilled.

What is the FOREX Market?

What is the FOREX Market?

The FOREX Market is the financial realm in which the trade and exchange of foreign currency systems takes place; the purchase(s) or sales of specific currency systems undertaken by individuals are conducted with regard to the fluctuation of respective fluctuation experienced by tradable and exchangeable currency – although its technical name is the ‘Foreign Exchange Market’, a multitude of traders is commonly refer to it as the FOREX Market.

What is the Virtual FOREX Market?

How Does the FOREX Market Work?

FOREX Market Legality